You’d be hard-pressed to find an angler in the Skeena region who hasn’t caught a bull trout or Dolly Varden, but you’d also be challenged to find one who is targeting these species. Yet, while most anglers are after Skeena steelhead and salmon, bull trout can also offer high-quality angling, especially during slower “shoulder” seasons.

In the spring, bull trout can be found aggressively feeding on out-migrating salmon smolts; in late fall, they move into salmon-spawning areas to feed on eggs and dying salmon. In addition, bull trout in many northern watersheds (like the Stikine and Dease rivers) grow big feeding primarily on Rocky Mountain whitefish, and can be caught year ’round.

Trout versus char – what’s the difference?

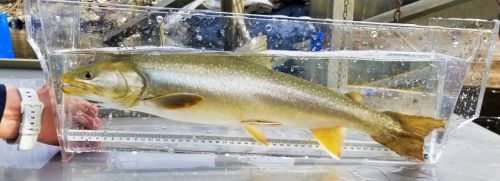

Bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus) is not actually a trout but a species of char that is most closely related to Dolly Varden, Arctic char, and brook trout. A good way to distinguish char from trout is the spotting pattern. In fresh water, char have light spots on a dark background; trout (including salmon) have dark spots and a lighter background. Trout also have teeth on the roof of their mouths, whereas char do not.

Although bull trout and Dolly Varden are different species, distinguishing between the two in the field is challenging where they co-occur, which applies in most of the Skeena region. Generally, bull trout are larger and darker in colour than the typically smaller and more silvery Dolly Varden, but this is not always the case.

Bull trout in the Skeena Region

Bull trout are found throughout almost all the Skeena region’s watersheds, ranging from small tributary streams to large lakes like Meziadin. While it might seem that bull trout are plentiful, with little conservation concern, closer examination (at least in some locations) suggests otherwise.

The bull trout is an exceptionally sensitive species, with strict habitat needs that include cold water temperatures, good water quality, and accessible migratory corridors. Increased water temperatures associated with a warming climate (already being observed in some inland rivers, like the Bulkley/Morice) challenge bull trout by increasing stress, delaying migration and spawning, and reducing growth rates, while also allowing fish more tolerant of warmer conditions to displace them.

Increasing resource development has created a plethora of access roads across much of the region that has negatively impacted rivers and tributaries inhabited by bull trout. Increased sedimentation of water associated with forestry practices and road construction can smother developing eggs, and reduce juvenile food sources. Fragmentation associated with culverts, road construction, and other linear developments can eliminate access to spawning and overwintering areas.

A bull trout’s aggressive demeanor makes it easy pickings for almost any angler. With greater angling access from these road networks, refuges from fishing that bull trout once had are no longer available, and existing regulations may not be adequate to protect populations. Elsewhere in North America, over-harvest of bull trout is (alongside habitat degradation and fragmentation) one of the main reasons this species has suffered declines. Provincial fisheries biologists are keen to prevent that here.

To ensure the fishing regulations can maintain sustainable populations, biologists are pursuing a multi-year investigation into the status of the Skeena region’s bull trout. By also improving their understanding of critical habitats, they hope to make sure that protection measures can support the full life cycle of this species. At the same time, they want to determine if some populations could provide more opportunities for anglers to harvest a fish.

The study

Starting in 2015, bull trout populations of the Morice, Gitnadoiks, Kitwanga, and Dease rivers, along with Meziadin Lake, were selected to study and compare.

- Morice River bull trout have been exposed to extensive, long-term development and high fishing pressure in this very accessible Skeena tributary.

- Gitnadoiks River, a lower tributary of the Skeena, is an interesting watershed as it is home to populations of Dolly Varden and bull trout which all exhibit multiple life-history strategies – including fish that remain as residents in the river and fish that migrate in and out of the river, possibly following an anadromous (searun) strategy.

- Meziadin Lake, in the Nass watershed, supports a unique (for the region) population of bull trout that grow in the lake but spawn in tributaries.

- Kitwanga River has a long-term salmon-monitoring program run by the Gitanyow Fisheries Authority that provides an opportunity to monitor abundance trends over time.

- Finally, the more northern population of bull trout from the Dease River in the Liard watershed was selected to compare against the other more-accessible populations which are thought to be at higher risk, or are more heavily fished.

Initial field work included redd surveys (stream-walks conducted to count nests of spawning fish) during the fall spawning period at key locations in the various rivers, as a surrogate way to estimate the abundance of adult fish. Over time, these counts can be compared to look for trends. In the Kitwanga River prior to 2018, it was assumed that only bull trout were being counted at the Gitanyow Fisheries sockeye smolt fence. However, as bull trout and Dolly Varden are very difficult to distinguish visually, it appears that both are using the river, complicating assessments. Most recently, high-reward tags were placed on bull trout in the Dease River and tributaries to encourage anglers to report catches.

Outcomes so far

Redd counts in the Morice watershed suggest reduced bull trout numbers compared to the early 2000s. In the fall, bull trout feed opportunistically on the eggs of spawning chinook, a key food source prior to overwintering. Biologists believe that recent lower abundances of chinook in this system may be a key reason for lower bull trout numbers, as their overwintering habitats appear to be mostly intact.

Additional studies are ongoing to disentangle the questions regarding species composition and reasons for movement in the Kitwanga River. It’s clear that char are migrating during salmon counts, but key questions remain. Are these fish from the Kitwanga River or elsewhere? Where do they go after leaving the Kitwanga? How many distinct populations exist, and what fisheries are they caught in? Answering these questions is important to ensure sustainable fisheries.

Due to their apparent low density and wide distribution, Dease River bull trout have been challenging to study. So far, biologists have tagged over 50 fish with $100 reward tags, and none have been recaptured. This suggests a large population and/or one that migrates over long distances. Biologists were able to expand the known distribution of bull trout to the upper Eagle River, where they had previously been undocumented.

To ensure spawning bull trout are not disturbed, fishing closures have been implemented where important spawning habitats were identified. Some modifications to regulations were also made to address the apparent declines in the Morice River population. However, increased angling opportunities are being considered for the Kitwanga River when counts of these char are high. Further management changes are expected as more information on these populations is obtained.

This blog series has been established as a way to inform freshwater anglers in B.C. about projects, such as this one, that their angling licence dollars support. In 2015, the Freshwater Fisheries Society of BC began receiving 100% (up from 70%) of all freshwater angling licence fees. With this additional funding, the Society committed to broadening the scope of its activities to include joint initiatives with the Provincial Government to support projects that benefit freshwater recreational fishing around B.C.

Author: Kris Maier, Fisheries Biologist, Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development.