There are over 20,000 lakes in B.C., varying from pond-sized to those with hundreds of kilometres of shoreline. It’s pretty safe to say that there are a few too many to ever fish in one’s lifetime! The Freshwater Fisheries Society of BC stocks about 800 lakes each year with rainbow, cutthroat, and brook trout, as well as kokanee. The majority of these stocked waters are situated in the southern half of the province. While many lakes in the province support wild populations of rainbow trout and char, most of these waterbodies are located in the northern half of the province.

Some of the best fishing for trout and char occurs in lakes or stillwaters with surface areas under about 400 hectares (1,000 acres). In terms of their ability to grow game fish, these productive lakes are located in the Interior in an area stretching from the southern Okanagan to the Peace River plateau.

Becoming a proficient fly fisher on these productive lakes means spending the time to learn how their ecosystems function. This includes the structure of the waterbody, what food sources are present, the preferred habitat of its trout, char, and other game fish species, and the best times of the year to catch these fish.

Compared to rivers and streams, lakes are much more secretive about offering hints where the trout are going to be found. With no currents to dictate where fish can live or determine their prime habitat, many fly fishers lack confidence when fishing lakes. We often refer to this as the black hole syndrome.

Understanding lakes can be like assembling a jigsaw puzzle: solve small pieces, and eventually you’ll have the complete picture. What follows are 10 tips to help put that puzzle together, which ultimately translates into having more success and fun on British Columbia’s almost limitless number of lakes. Of course, these tips apply to productive stillwaters anywhere.

1) Learn where the trout live

Lakes can be broken into three distinct areas or habitat zones.

The shoal or littoral zone is the shallow-water area of the lake. This is the water from the shoreline out to a depth of about 7.5 metres (25 feet). This also coincides with the maximum depth of sunlight penetration (a key factor in determining overall lake productivity). A shoal is where vegetation grows and where the majority of aquatic food sources is found. A shoal is like a grocery store where trout and char come for food. It is the most important area of a lake when it comes to catching trout.

The drop-off zone is where the edge of the shoal zone transitions to the deeper parts of the lake. The slope of the drop-off can be gradual or quite steep. Drop-offs are also the maximum depths of green plant growth, and are perfect feeding areas for fish. Drop-offs also offer refuge from the warmer shallow waters during the hot summer months. This habitat zone is relatively short or narrow as the water quickly deepens into the deepwater zone of a waterbody.

The deepwater zone supports the least number of macroinvertebrates (insects and other larger food sources). However, in many lakes, the deepwater or mid-lake zone supports fairly prolific chironomid populations and their subsequent emergences.

2) Watch the birds

Aquatic insect hatches can often be confined to particular shoals or specific locations within a lake. Often, on larger waterbodies, a certain colour of chironomid can be emerging in one bay, and a totally different size and colour pupa emerging in another. Birds (like swallows, terns, gulls, and night hawks) can find emerging chironomids, mayflies, and caddisflies, as well as other hatching insects, much more quickly than we can. Binoculars are invaluable for seeing avian activity, especially when fishing larger lakes.

3) Look on and into the water

Carry a small aquarium net to capture pupae, nymphs, emergers, and adult insects so you can match fly patterns to size and colour. Place the specimens in a vial or white dish to get a better idea of colour, and to also watch the actual emergence process. Surface and subsurface feeding trout leave distinct riseforms that provide clues to the angler as to what insect stage they are selecting. Trout that are feeding on minnows often show chasing/slashing rises as they work through the school of baitfish. And finally, polarized sunglasses will allow you to see better beneath the surface to spot shoals, drop-offs, spring areas, and bugs.

4) Know your insects and other food sources

Learn to recognize the major aquatic invertebrate food sources that make up a large percentage of the diet of trout. Food sources include species like chironomids (midges), mayflies, caddisflies, damselflies, dragonflies, water boatmen, backswimmers, scuds, leeches, snails, and forage fish. It is equally important that you have a sound understanding of their individual life cycles and habitat requirements. Getting to know a particular lake or group of lakes translates into learning which food sources are present,and knowing the emergence sequences peculiar to those individual waters. Many good reference books cover identification, life history, and distribution of the most common stillwater invertebrates. These insects’ life cycles and emergence patterns are similar regardless of where a lake is geographically located. Chironomids from a lake in the Northwest Territories emerge the same way as those in a lake on the north island of New Zealand.

5) Water temperature

Water temperature influences the hatches, and each insect order has preferred temperature ranges for development and emergence. Insect hatches follow a sequence that typically begins with midges, followed by mayflies, then damselflies, caddisflies, and lastly dragonflies. The most intense emergences typically occur when surface water temperatures range between 10° and 18° C (50° and 65° F). It is possible to see multiple insect orders and species emerging at the same time, which can be confusing to both angler and fish. Anglers must rely on their knowledge of individual insect emergence strategies, and be prepared to present all options to those feeding fish.

6) Basic fly lines

Stillwater anglers should be prepared to present flies from the surface to depths of over 12 metres (40 feet). An understanding of the life cycles of individual insect orders will dictate what depth zones may be fished when that particular food source is emerging or is readily available.

Floating fly lines cover the shoal zone, and are ideal for presenting floating, emerging, pupal, and nymphal imitations. A slow or intermediate sinking line is good for fishing the deeper parts of the shoal, such as water depths between three and six metres (10 and 20 feet). This line allows slow presentation of pupal and nymphal patterns while ascending at a gradual angle towards the surface. A fast or extra-fast sinking line provides good coverage of the six- to 12-metre (20- to 40-foot) depth range, and is useful for fishing dragonfly nymphs, leeches, and shrimp along the deeper edges of drop-offs, or retrieving flies up the face of the drop-off.

7) Fly selection

Do some homework to learn what insects and other food sources are in the stillwaters you will be fishing. Local fly shops, fly-fishing clubs and regional fishing guidebooks are good sources for this information. The ideal fly box will have both generic imitations of food sources and some refined patterns that more closely imitate the various life stages of insects found specifically in those waters. There are many good commercially-tied fly patterns covering all the important food sources of trout and char. It is no longer a disadvantage to not being a fly tier. Basic subsurface patterns that should be in your stillwater fly box include leeches in black, maroon, and dark green, with and without beadheads; dragonfly and damselfly nymphs in light and dark olive body colours; shrimp or scud patterns in light olive to dark olive; mayfly nymphs in dark brown to tan; caddis pupae in medium green to brown body colours; and finally, a selection of chironomid pupae. Must-have chironomid pupal pattern colours include black, brown, green, and maroon with abdominal ribbings of copper, red-copper, silver, or gold wire. Add a few dry flies (such as Tom Thumbs to imitate the adult caddis; Parachute Adams for adult mayflies; and the Lady McConnell for imitating the adult chironomid).

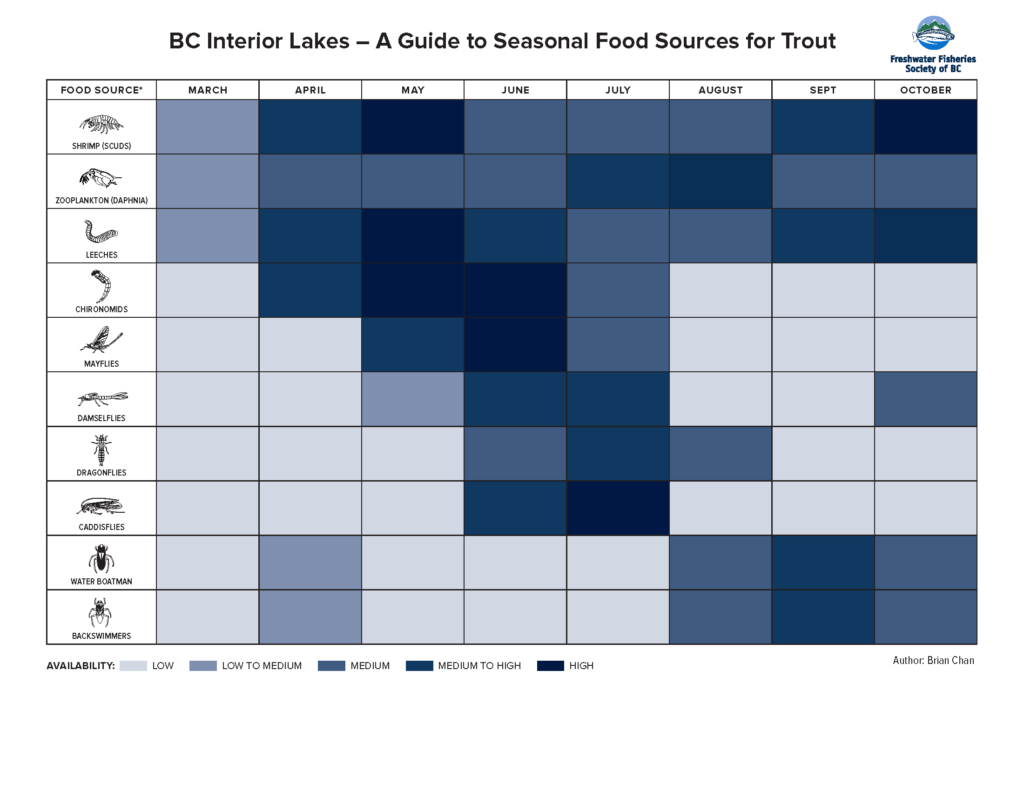

Match the hatch. Use the following chart as a guide to know what is hatching, and when.

8) Proper boat set-up

A stable flat-bottomed boat or pram is often the most effective way to fish the smaller trout lakes. The biggest advantage to a hard-bottomed craft is that you can stand up,and look out over and into the water. This is a particular advantage when fishing clear-water lakes, as you can spot individual fish or schools of fish, and you can observe their feeding behaviour and patterns of movement. Pontoon boats are another good choice, as the angler sits high enough in these craft to see into the water. Some pontoon boat manufacturers are now offering standing platforms. Both boats and pontoon boats can be moved from area to area much faster than a float tube. This can be critical when trying to locate specific insect emergences when fishing larger waterbodies. Hatches can occur at one end or bay of a lake and be non-existent in another location.

Another essential tool for the stillwater fly fisher is a depthsounder or fishfinder. You need to know the depth you’re fishing at so that the right flies can be presented in that depth zone. Depthsounders are relatively inexpensive, yet highly sensitive instruments. Things to look for in a sounder include the transducer cone angle, which should be at least 50° wide or wider. This allows greater coverage of the bottom structure under the boat, and thus increases the chance of marking fish. Remember, the majority of fly-fishing done in productive lakes is in water less than about eight metres (26 feet) in depth, and often in less than five metres (16 feet). Consider the power source of the sounder, as some units can go through smaller-sized batteries at a very fast rate. Many sounder units come wired to run off a large 12-volt battery (like one used to power an electric motor).

Fishing out of a boat can be noisy, especially one made out of aluminum. Reduce the chances of scaring fish by fitting outdoor carpeting over the floor of the boat. Always keep in mind that sound travels far and fast in water, and trout have sensitive hearing systems.

9) Double anchoring

When fishing out of a boat, it is critical to have anchors out both bow and stern. This is especially important if there are two people fishing out of the same craft. Double anchoring prevents the boat from swinging back and forth when the wind is constantly changing direction. A stationary boat allows the best control of fly lines and retrieves. It is important to have as straight a line connection as possible between the fly rod, fly line, leader and fly so that even the softest bite can be detected. Simple anchor-control pulley systems make lifting, storing, and re-setting anchors easy while at the same time requiring little movement within the boat.

10) Learn about preferred food sources

Trout that become focussed on a few dominant food sources in a lake can often become difficult to catch. Small, nutrient-rich lakes often support immense chironomid and scud populations. Anglers who have consistent success in these waters have learned the details of the life cycles and habitat preferences of these food sources. For instance, when chironomid pupae suspend just centimetres off a lake bottom (often for several days, as they complete the transition from the larval to pupal stage), there can be great fishing even though there is no sign of any emergence at the surface.

When searching out a new lake, slowly troll or drift and cast around the basin while getting a good look at shoals, drop-offs, weed beds, and perhaps sunken islands. Dragonfly nymphs and leeches are always good searching patterns. Both invertebrates are common inhabitants of lakes, and both are big food items. Don’t be afraid to try flashy or bright patterns like bead-headed woolly buggers, and be prepared to vary speed and direction frequently when either trolling or retrieving a cast fly.

Author: Brian Chan, Fishing Advisor, Freshwater Fisheries Society of BC

Photo Credit: Steve Olson, Brian Chan, Noel Fox.